There is nothing quite like the pleasure of biting into a fresh, crisp apple. That burst of flavor, texture, and sweetness is unarguably one of life’s simple pleasures. But have you ever wondered what journey that apple undertook before it arrived in your hand? Or what causes it to transition from crisp to mushy? This easy-to-understand article is designed to satisfy your curiosity by uncovering the mystery behind the lifecycle of an apple. It delves into the anatomy of an apple, the ripening process that results in the perfect blend of taste and texture, the science behind its decay, and crucially, tips to extend its shelf-life while maintaining its desirable crispness.

Understanding Fresh Apples: Anatomy and Composition

Understanding the Basic Anatomy and Composition of an Apple

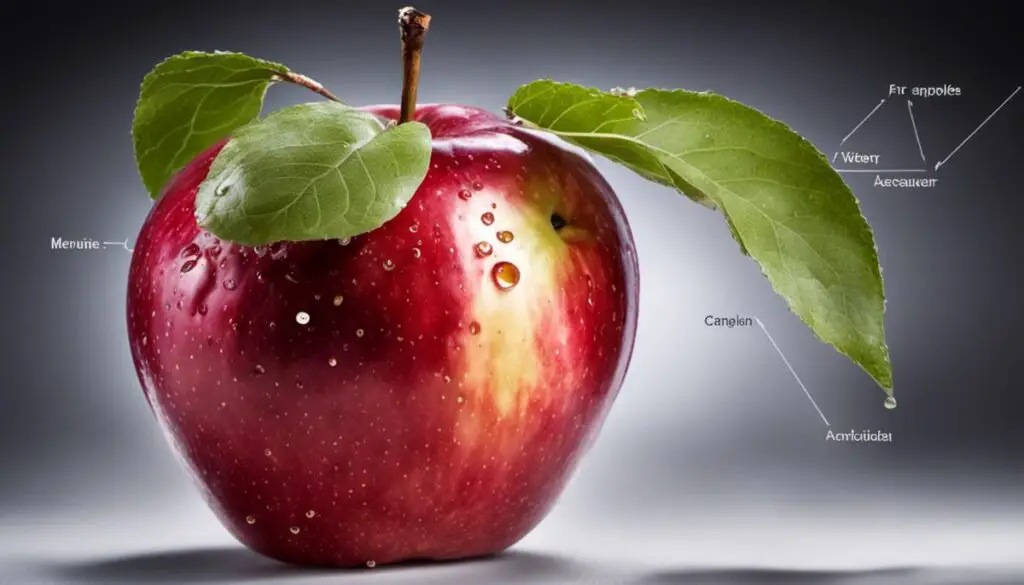

A typical apple is composed of three major parts—the skin, the flesh, and the core. Of these, the crispness of an apple is primarily determined by the flesh, or the parenchyma tissue to use the correct biological term. This tissue is laden with water, contributing to the texture and juiciness of the apple. This series of cells are like tiny compartments full of water, and the cell walls provide the resistance against your teeth when you bite down, which creates the distinctive crunch of an apple. The type of apple, its freshness, and its storage conditions all affect the apple’s water content and, therefore, its crispness.

Different Varieties of Apples and Their Crispness Levels

Apples come in thousands of varieties worldwide, each with its unique texture and crispness. Some apples like Honeycrisp, Granny Smith, or Fuji are known for their high crispness levels. These varieties have a firm flesh that feels dense, and biting into them makes a satisfying crunch sound. Others, such as Red Delicious or McIntosh, have a softer texture and may not be as crisp. Indeed, these variations occur because different apple varieties have different cellular structures, water content, and sugar levels, impacting their texture and firmness.

The Impact of Water Content on Apple’s Texture

Water content plays a pivotal role in maintaining an apple’s crispness. The cells in an apple’s flesh are essentially tiny water balloons. When an apple is ripe and fresh, these cells are full of water, giving the apple its firm texture. As an apple matures or is stored, the water gradually seeps out of the cells through a process called senescence, leading to a loss of crispness. Ultimately, when these cells lose their water, the apple becomes soft or even mealy. To keep apples crisp, it’s crucial to store them in the right conditions to slow down the senescence process.

The Role of Cell Structure in the Texture of an Apple

The cell structure of an apple also plays a significant role in determining its texture. Firm, crisp apples typically have larger cells that are tightly packed together. When bitten, these cells shatter, releasing their juice and giving a satisfying crunch. Over time, or if stored improperly, the cell walls start to degrade due to enzymatic actions, causing the cells to rupture and the apple becomes softer. This process is a common way that apples lose their crispness and become mushy.

Diversity in Apple Varieties and Texture Influence

Apple varieties abound, each with a unique consistency due to their specific composition. For instance, the tart Granny Smith apples, celebrated for their abundant acid content, preserve their structure longer than most varieties, leading to their iconic crispiness. Alternatively, Golden Delicious apples, characterized by their thin skin and reduced acid content, are naturally softer and susceptible to becoming mushy. These differences make certain apple types ideal for baking, where a softer texture is preferred while others are tastier when enjoyed fresh and crisp.

What Causes an Apple to Ripen

Transitioning From Green to Ripe: A Look at the Apple’s Transformation

An apple embarks on its ripening journey on the tree and continues evolving to full ripeness even after being plucked. The ripening process is initially signaled by a color transformation, changing from the initial green to potentially a mix of red or yellow in the fully mature apple, depending on the specific type.

This color change aligns with significant alterations in the flavor, aroma, and texture. As they ripen, apples transition from an initially tart, slightly bitter taste to a sweeter, more robust flavor. This sweetness is a direct result of starch reserves in the apple converting to sugar, a process driven by the enzyme, amylase. The sugars then mingle with the apple acids to produce the unique sweet-tart flavor that ripe apples are known for.

Along with these changes, the apple’s aroma also evolves, becoming more potent as the apple ripens. Compounds known as “esters” and “aldehydes” drive this increase in the fruit’s aroma.

Role of Ethylene in Ripening

Key to the apple ripening process is ethylene, a hormone produced naturally by the apple. Ethylene acts as a biochemical trigger to accelerate the ripening process. Fruits, like apples, which produce ethylene as they ripen are known as climacteric fruits. Increased ethylene production is the reason why storing apples with other fruits can cause them to ripen and spoil faster.

Texture Transition in Maturing Apples

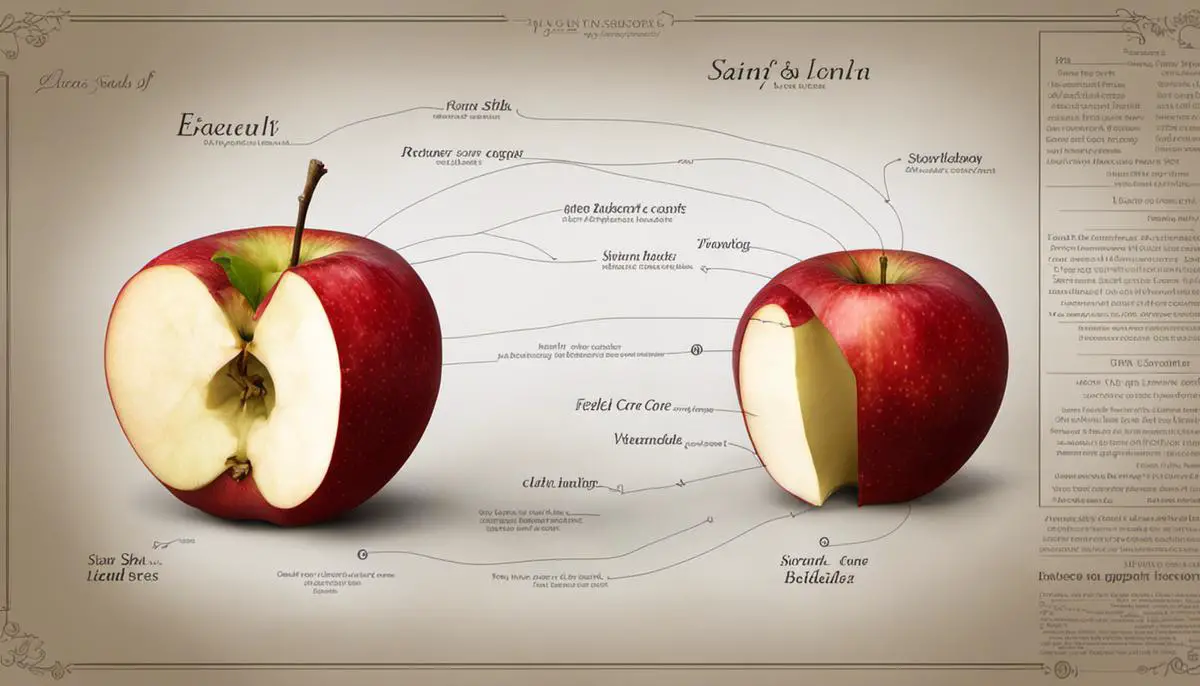

During the ripening process, apples undergo a noticeable change in texture. Predominantly, two enzymes known as pectinase and cellulase are responsible for this endeavor. These enzymes break down the cell walls and the pectin found within them as the apple ripens. Consequently, the apple’s composition undergoes a transformation, which entails a gradual softening of the flesh as the firm structures inside start to deteriorate.

Upon biting into a fresh, crisp apple, you experience a delightful crunch, thanks to a considerable portion of cells inflated with water, held tightly together by pectin. In contrast, with an overripe, or more appropriately, mushy apple, this firm edifice is lost due to enzymatic disintegration of pectin and the cells. This chain of events results in an easily squished texture, signaling an overripe apple. Variables such as temperature and ethylene concentration significantly impact the rate and degree of this textural transformation.

While the ripening process enhances the apple’s natural sweet and flavorful crunch, it’s a bittersweet victory as it simultaneously detracts from the apple’s firmness. If an apple has turned particularly mushy, it’s frequently interpreted as a sign of overripeness and the commencement of decay – the result of both enzymatic reactions and infestation by bacteria or fungi.

In essence, the metamorphosis in an apple’s texture from crisp to mushy is primarily governed by enzyme activity and ethylene production. While this journey may sound unsavory in culinary terms, it is a natural facet of an apple’s life cycle, emblematic of its ripening progression.

The Science of Apple Decay

Regulation of Enzymes in Apples

Plucked fresh from the tree, an apple is packed with robust texture and flavor. A cadre of enzymes known as pectin methylesterases (PMEs) are instrumental in preserving this desired state as they uphold the rigid cell walls’ structure within the apple, imparting it a firm texture. However, the beginning of ripening marks the stage at which PMEs start converting the pectin contained inside apple’s cell walls into smaller molecules.

This initial breakdown of pectin sets off a chain reaction further leading to the progressive softening of the apple. Another enzymatic player, polygalacturonase (PG), kicks into action as the apple matures, stimulating the pectin’s disintegration at an even faster pace, subsequently leading to an increasingly soft texture. Intriguingly, this enzymatic transition is naturally pre-programmed to spring into action once the apple attains full ripeness, thus making the apple more alluring to prospective feeders who might devour the apple and scatter its seeds.

Fermentation and Bacterial or Fungal Infections

Once an apple gets overripe, other biological processes speed up its decay. On exposure to oxygen, the sugar within the apples can start to ferment due to yeast. Fermentation leads the apple’s sugars to convert into ethanol and carbon dioxide, giving off a characteristic sour smell.

If the apple’s barrier, the skin is broken or bruised, it can get invaded by bacteria and fungi from the environment which proliferate in the sugary, wet interior of the fruit. Fruiting bodies of mold or bacterial colonies can lead to visually noticeable rot, changing the apple’s texture to mushy or slimy, and the color to brown or green.

Certain bacteria and fungi specifically contribute to the rotten apple’s smell. For instance, bacteria known as Erwinia amylovora causes a condition in apples called fire blight that produces a faint, unpleasant odor.

Role of Temperature and Humidity in Apple Decay

Environmental factors such as temperature and humidity also play vital roles in the apple’s transition from crisp to mushy. High temperatures speed up the activity of degrading enzymes and encourage rapid bacterial and fungal growth. On the other hand, cold temperatures slow down the enzymatic activity and microbial growth. That’s why storing apples in a fridge helps them stay fresher for longer.

Humidity also affects the apple’s crispness. In a very dry environment, moisture inside the apple will start to evaporate, causing the apple to dehydrate and shrivel. While it might not turn mushy, it loses its plumpness and crispness. In contrast, in a damp environment, excess moisture hastens bacterial and fungal growth, leading the apple to become overripe quickly and turn mushy.

Wrapping Up

When an apple shifts from a crisp to a more mushy state, it’s due to a mix of the fruit’s inherent ripening course, microbial invasions, and varying environmental influences. With a deeper comprehension of these factors, we have the power to better manipulate them in order to prolong the lifespan of the fruit. This helps decrease waste while improving how we consume and store apples.

Preventing Apple from Turning Mushy

Grasping the Transformation in Apple Textures

This softening transition is brought on by a biological process known as ripening, as well as exposure to fungi and bacteria present in the environment. As the apple ripens, specific enzymes within the fruit start breaking down its cell walls and the pectin, which is a substance responsible for binding the cells together. Over time, this process gradually erodes the apple’s firm framework, resulting in it becoming softer and mushier.

Proper Storage Methods to Prolong Apple Freshness

The simplest method to ensure an apple’s crispness remains is by proper storage. Keeping apples refrigerated can slow the ripening process. Moreover, always handle them gently to minimize bruising, as damaged areas can speed up the ripening. For longer periods, apples can be stored in the crisper drawer of a refrigerator in a plastic bag with holes to provide air circulation but must keep them away from other fruits and vegetables. The ethylene gas emanated from apples can speed up the ripening of other produce.

Temperature Control for Crisp Apples

Maintaining the right temperatures can play a vital part in keeping an apple’s texture intact. Warm temperatures catalyze the ripening process, hence, to retard this process; apples should be kept at a cold temperature ranging between 30-32°F. Note that avoiding complete freezing is crucial.

Importance of Humidity and Air Circulation

Alongside temperature, controlling humidity is just as crucial, high humidity is essential for apple preservation since it prevents the fruit’s moisture loss, hence preventing shriveling. Excellent air circulation helps even distribution of temperature and humidity, thus minimizing the manifestation of rot or decay.

Choosing the Right Varieties and Picking at the Right Time

Not all apple varieties have the same shelf life. Varieties like Red Delicious, Fuji, and Granny Smith can be stored for longer compared to other types. If you have apple trees, picking them when they’re mature but not fully ripened can also make a difference as fully ripened apples tend to go mushy faster. Look for the change in color and a subtle softening as indications of mature apples.

Waxing Apples for Extra Protection

A layer of edible wax can add additional protection to the apples by sealing moisture in and reducing the exchange of gases, thus slowing down the ripening process. Many apples available in markets come pre-waxed, but you can also apply food-grade wax at home.

Recognizing that an apple’s texture transformation is a part of their natural life cycle can help strike a balance between storing apples for crispness and enjoying them at peak ripeness. While these methods can delay the softening of apples, keeping in mind that enjoying apples at their perfect ripening point offers the best taste and texture.

Exploring the life of an apple from the tree to the table has led us through an intriguing journey. These insights have unveiled the scientifically subtle yet profound transformations which an apple undergoes in its lifetime. Not only does this information appeal to our curiosities, but it also equips us with practical knowledge we can use to maximize our apple-eating experience. Specifically, the understanding of ripening and decay process along with effective storage methods can extend the life of our apples. So, the next time you enjoy a fresh and crisp apple, you’d acknowledge the journey it made to be this healthy and delightful delight!